Understanding Group Actions on Sets

Every first encounter with the notion of group action is confusing. How can group and set elements interact with each other? The idea of a binary operation between the elements of a group and a set seems to be way abstract at first, but let’s dive deeper into it.

We will start with some simple examples. Let’s consider the multiplicative group \((\mathbb{Q}\setminus \{0\}, \cdot)\) and the set \(\mathbb{R}\) of the real numbers. If we pick the integer \(g=2\) from our group, then for every real \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) we can define the binary operation \(*\) between our group and our set such as:

\[2*x = 2x\]where on the right side is the usual multiplication. So nothing really fancy happening in this example, right? We should notice, however, that the random integer \(2\) we picked (any other element from our group works just fine) permutes every real (every element of our set) to another real (another element of our set).

Keep the word permutation in mind. Let’s consider now the symmetrical group \(S_n\) of \(n\) elements and the set \([n] = \{1,2,\ldots,n\}\). Let’s fix an element \(\sigma \in S_n\). Now, for every \(i \in [n]\) we can define the binary operation \(*\) between our group and our set such as:

\[\sigma * i = \sigma (i)\]We are literally just permuting the elements of \([n]\) the way \(\sigma\) does. But \(\sigma\) is by definition a permutation of \([n]\), so this whole example is just a tautology. In a sense, the group element we choose defines the way it will permute the elements of our set. That is what’s really happening. Let’s revisit the formal definition now.

\(\text{Definition. Let } G \text{ be a group and } X \neq \varnothing \text{ a set. A (left) group action of } G\) \(\text{ on the set } X \text{ is a function } G \times X \rightarrow X, (g,x) \mapsto g*x \quad \text{ such that: }\)

\[1_G * x = x \quad \text{ for all } x \in X.\] \[(g_1 \cdot g_2) * x = g_1 * (g_2 * x) \quad \text{ for all } x \in X \text{ and } g_1,g_2 \in G.\]So what do these conditions mean? Let’s take our first example into account again. If we permute a real \(x\) by \(2\) and then permute the real \(2x\) by \(3\) it has to be the same as permuting \(x\) by \(2\cdot 3 = 6\) from the very beginning. Of course, in this example when we say permute we really mean multiply. So the second condition pretty much says that the way \(g_2\) will permute \(g_1 *x\) must be the same as the way the group element \(g_2 g_1\) will permute \(x\).

Now, what about the first condition? This one implies that the identity element of our group should map any element of our set to itself. What this means is that the identity element induces the identity permutation of the set X. But wait! now if you think about it, every element \(g \in G\) induces a permutation of the set \(X\).

What we really are defining is a group homomorphism \(\rho : G \rightarrow S_X\) where \(S_X\) is the symmetrical group of the elements of \(X\). The homomorphism \(\rho\) takes an element \(g \in G\) and maps it to a permutation \(\rho_g :X \rightarrow X\) which is defined as \(\rho_g (x) = g * x\). The reader should try to verify that indeed \(\rho\) is a group homomorphism and every \(\rho_g\) is indeed a permutation of \(X\).

We can see that this group homomorphism and our group action are pretty much the same thing. For every group homomorphism \(\rho : G \rightarrow S_X\) we can define a group action on \(X\) by \(g* x = \rho (g) (x)\).

Let us now consider some more interesting examples.

In Galois theory we deal with roots of polynomials over fields. Most of the time these fields contain \(\mathbb{Q}\). We also denote \(\mathbb{Q}(a_1,\ldots,a_n)\) the smallest subfield of \(\mathbb{C}\) that contains \(\mathbb{Q}\) and \(a_1,\ldots,a_n\). Lets consider the polynomial \(x^4 +3\). This polynomial splits completely over \(K = \mathbb{Q}(a,\zeta_4)\) where \(a = i\sqrt[4]{3}\) and \(\zeta_4\) is a primitive 4th root of unity. What this means is that in the polynomial ring \(K[x]\) have the factorization into linear factors:

\[x^4 + 3 = (x-a)(x- \zeta_4 a)(x-\zeta^2_4 a) (x-\zeta^3_4 a) =\] \[=(x-a)(x-ia)(x+a)(x+ia)\]Lets consider our set \(X\) to be the four roots of this polynomial and our group in this example will be

\[G = Gal(K/\mathbb{Q}) =\] \[= \{\sigma : K \rightarrow K | \quad \sigma \text{ is an automorphism of } K, \quad \sigma(q) = q \quad \forall q \in \mathbb{Q} \}\]where the group operation is the usual function composition. Therefore, our group action this time is simply:

\[G \times X \longrightarrow X\] \[(\sigma , x) \longmapsto \sigma(x)\]So we are pretty much permuting the roots of the polynomial. Another way to see this is if \(b\) is a root of a polynomial with coefficients over \(\mathbb{Q}\) such as:

\[a_n b^n + a_{n-1} b^{n-1} + \ldots + a_1 b + a_0 = 0\]then applying an automorphism \(\sigma\) such that \(\sigma(q) = q\) for every \(q \in \mathbb{Q}\), using the facts that \(\sigma(x + y) = \sigma(x) + \sigma(y), \quad \sigma(xy) = \sigma(x)\sigma(y)\), we will get:

\[a_n (\sigma(b))^n + \ldots + a_1 \sigma(b) + a_0 = \sigma(0) = 0\]and therefore \(\sigma(b)\) is another root of the same polynomial! But we are not really permuting the roots in every possible way. Since \(\zeta_4 = i\) and \(i^2 = -1\) is a rational number, then \(\sigma(i)^2 = \sigma(i^2) = \sigma(-1) = -1\). So we can only map \(i\) to itself or to \(-i\). Since \(a^4 = 3\) is a rational as well and it has to stay fidex, we can pretty much map \(a\) only to itself, \(-a, ia,-ia\). Taking for granted the standard fact in Galois Theory that the automorphisms of \(K\) that preserve \(\mathbb{Q}\) are fully defined by where they map the elements \(a,\zeta_4\), we get that our group \(G\) is isomorphic to \(D_4\), the dihedral group with 8 elements.

One could argue that this underlying group action, the ways of permuting roots of polynomials, is the essense of Galois Theory. If \(X\) is the set of roots of an irreducible polynomial in \(\mathbb{Q}[x]\) then \(Gal(\mathbb{Q}(X)/\mathbb{Q})\) is isomorphic to a subgroup of \(S_n\) where \(n\) is the number of distinct roots. Just like in our previous example! \(G\simeq D_4 \simeq <(1234),(12)(34)>\) which is a subgroup of \(S_4\).

In all this lies the reason of why we cant solve 5th degree polynomials with radicals. Polynomials of degree 5 induce groups \(Gal(K/\mathbb{Q})\) that are isomorphic to subgroups of \(S_5\). Depending which subgroup we are talking about, problems arise along with the fact that the group \(S_5\) is not [solvable]{https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solvable_group}. If there was a formula solving all 5th degree polynomials, that would contradict the previous fact.

We will consider one last interesting group action example until the end of this post. With some taste of combinatorics. The dihedral group 4 \(D_4\) we mentioned previously is the group of symmetries of the square. The group presentation is \(D_4 = <a,b: a^4 = b^2 = e, ab = ba^{-1}>\). So we could say the group elements are \(\{e,a,a^2,a^3,b,ba,ba^2,ba^3\}\). What does this mean visually?

There’s a hidden group action in there. What if we consider the vertices of the square to be distinct e.g. if we color them with different colors. In the way the above animations work, the group \(D_4\) acts on the set of the ordered tuples corresponding to the square vertices such as:

\[e * (1,2,3,4) = (1,2,3,4)\] \[a * (1,2,3,4) = (2,3,4,1)\] \[a^2 * (1,2,3,4) = a * (2,3,4,1) = (3,4,1,2)\] \[\text{ etc.}\]Let’s formalize this a bit more. Let \(A\) be a set of \(m\) elements and \(X\) be the set of all functions (colorings)

\[f:A \longrightarrow \{k_1,k_2,\ldots,k_n\}\]where we map every element of \(A\) to a color \(k_i\).

The symmetrical group of \(A\) is isomorphic to the symmetrical group \(S_m\) using the relation:

\[(\sigma f) (a) = f(\sigma^{-1}(a)), \quad a \in A, f \in X \text{ and } \sigma \in S_A\]But what does this relation mean? We want to decide how to permute a coloring \(f\) by \(\sigma\), so we are looking at the colors of each element \(a\). The element \(\sigma^{-1}(a)\) is another way of saying the previous element of a (or color) before permuting by applying \(\sigma\). Moreover, \(f(\sigma^{-1}(a))\) is just the color \(f\) applies to this previous element of \(a\). So this relation means that if \(\sigma(b) = a\) then the new coloring \(\sigma f\) applied to \(a\) will just be the color of the element \(b\)!

Feel free to verify that \((ef)(a) = f(a)\) and \(\sigma (\tau f)(a) = (\sigma \tau) f(a)\)!

Looking back at the animations now knowing this, let’s consider that \(A = \{1,2,3,4\}\) and that our colors match their numbers e.g. \(f(a) = a\). Now, what we are really saying is the action of an element \(g\) on the color of our vertex \(f(a)\) is just the color \(\rho_g (f(a))\). So in our example:

\[a * (1,2,3,4) = (2,3,4,1) \quad \text{ induces the permutation: }\] \[\rho_a (1) = 2,\quad \rho_a (2) = 3,\quad \rho_a(3) = 4, \quad \rho_a(4) = 1\] \[\text{ or just } \rho_a = (1234)\]So that’s pretty much what group actions are. The elements in \(G\) decide in what way we are going to shuffle the elements in \(X\).

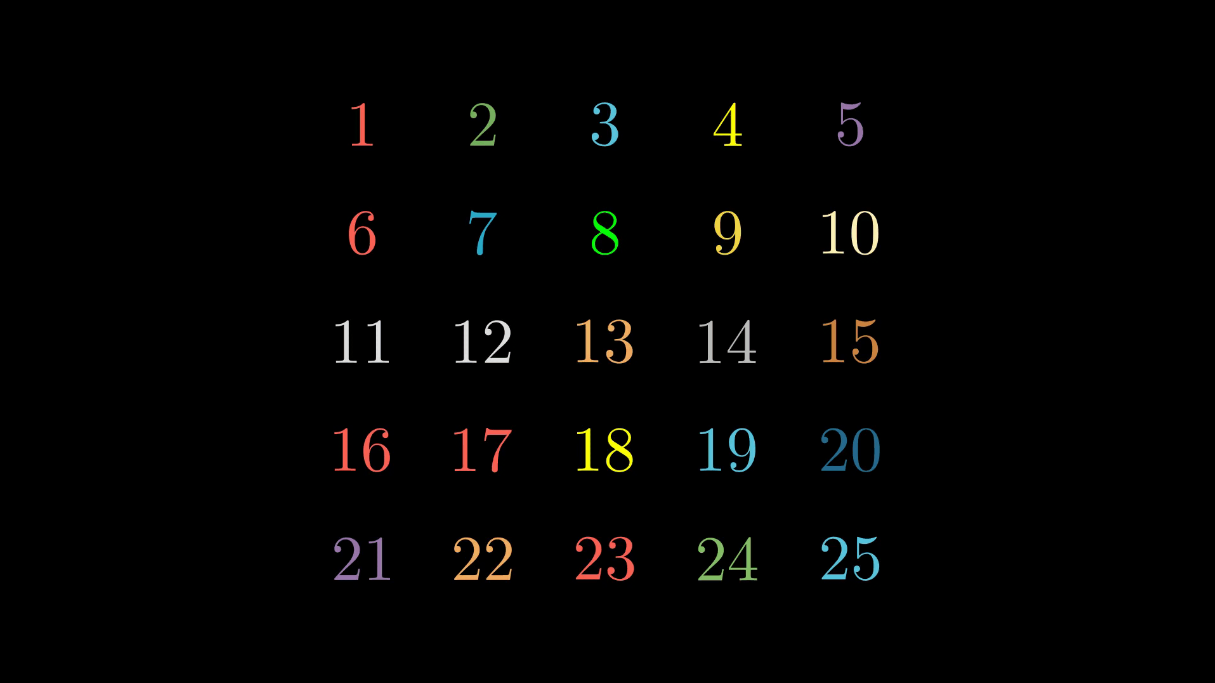

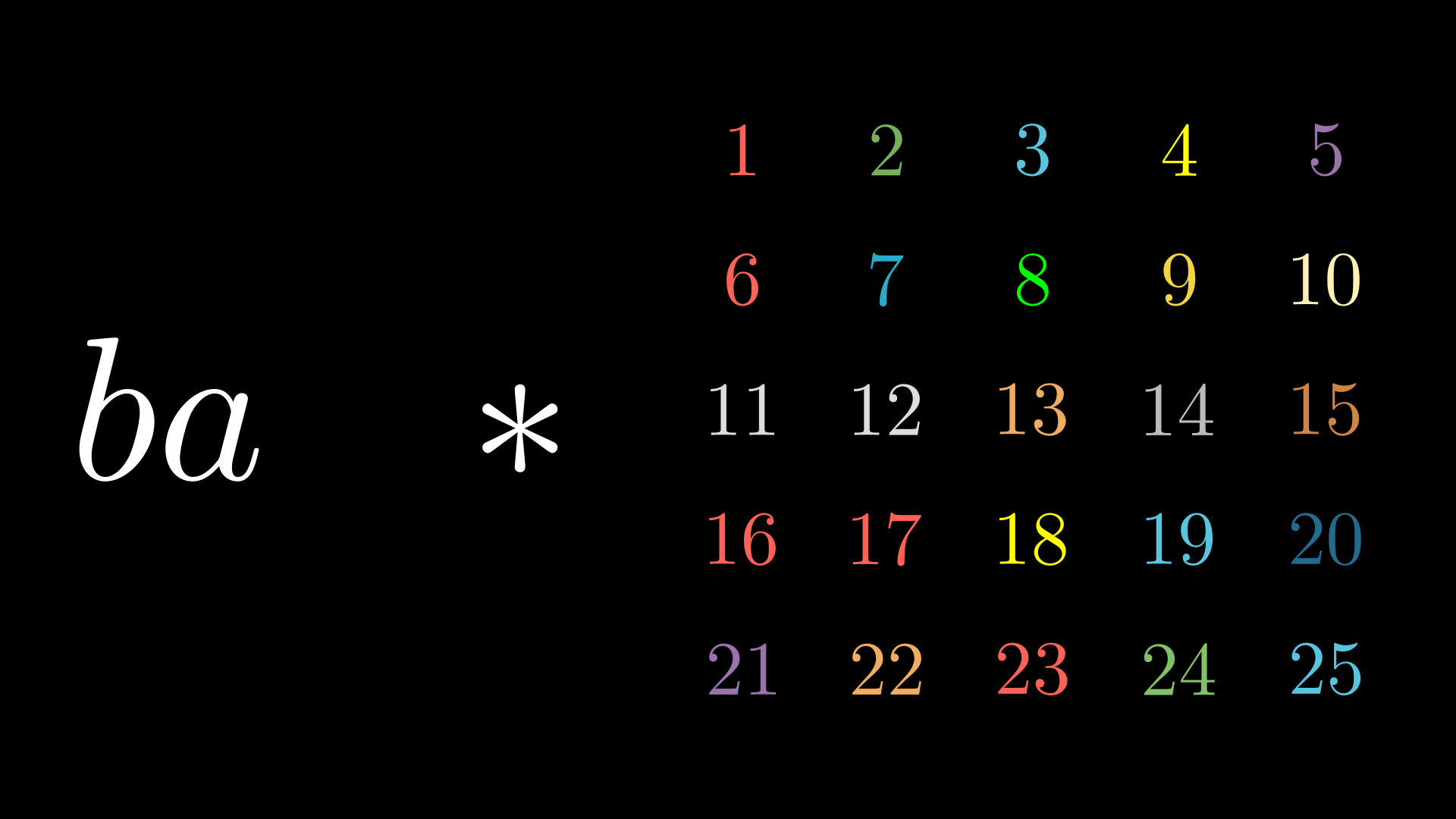

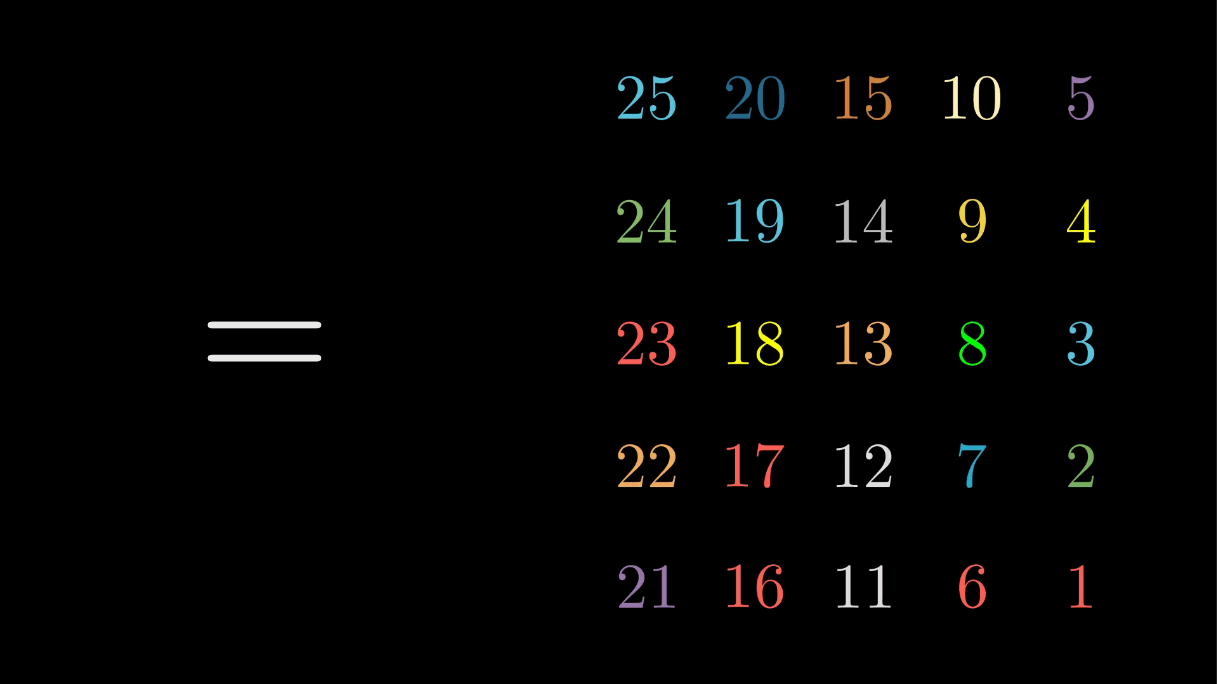

Let’s solve a neat combinatorics problem now. Suppose we have a \(5 \times 5\) grid and we want to color each cell with one out of \(n\) colors.

In how many was can we do that? The answer of course is \(n^{25}\). That’s easy. What if we decide that two colorings of our grid are equivalent if the second one can happen from the first after a \(90^{\circ}\) rotation or a reflexion over any axis of symmetry? How many equivalence classes of colorings are now? The answer is \(\frac{1}{8}\left(n^{25} + 4n^{15} + 3n^{7}\right)\). Not so straightforward this time, right?

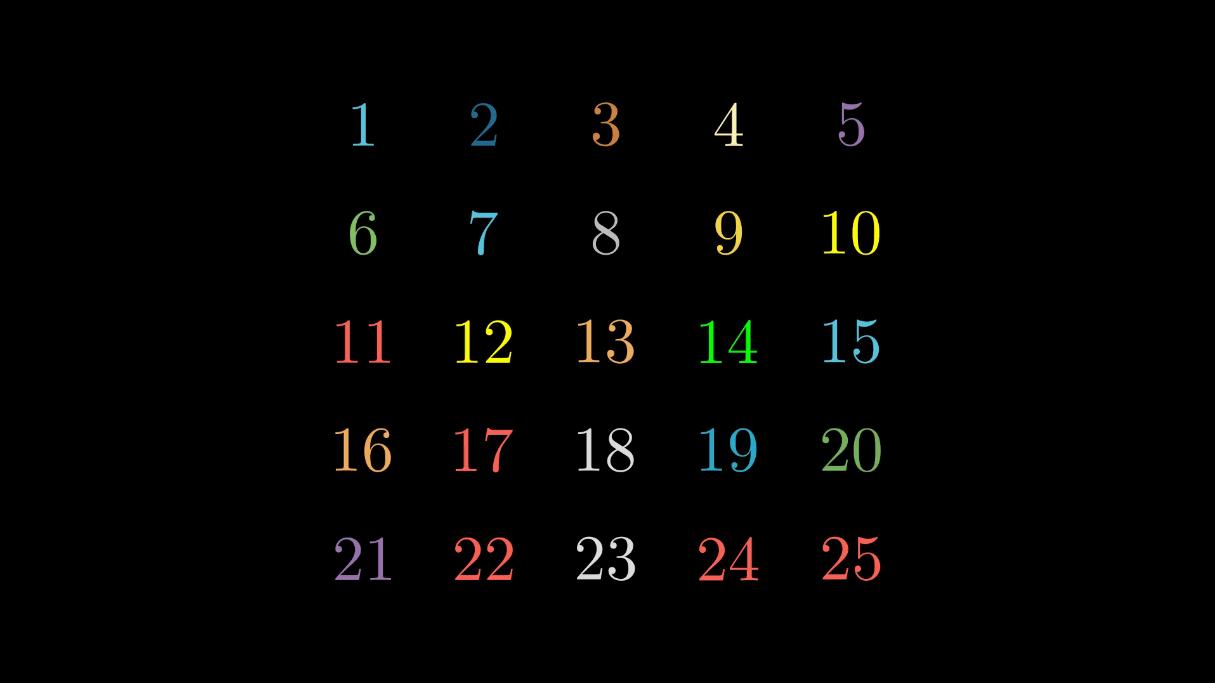

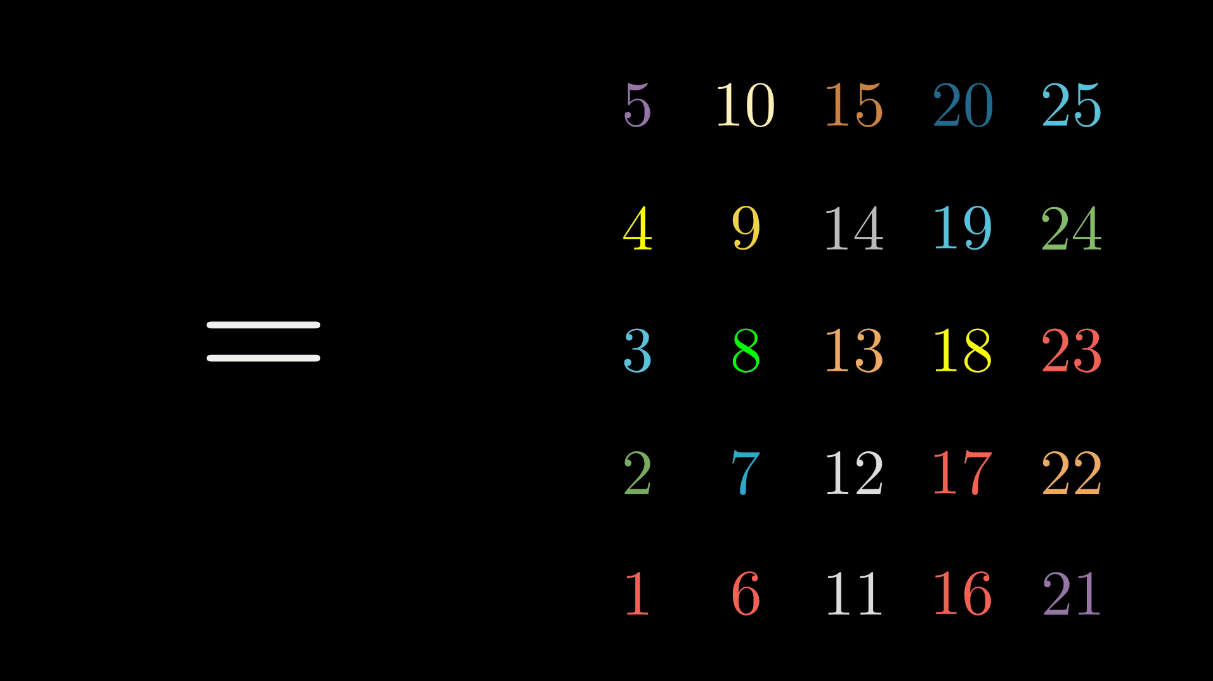

For example, the following two colorings are equivalent:

We can see that the second coloring is the reflection of the first one on the \(y=x\) axis. Or with our \(D_4\) notation its just the element \(aba^2\) acting:

Notice that in the last frame the colors match exactly with the colors in the second picture.

So how can we deduce this result? Truthfully, we haven’t covered all the necessary material of group actions as we only dwelled on the definition. We will rely on the famous Burnside’s Lemma for the answer.

\[\text{Burnside's Lemma.}\] \[\text{Let } G \text{ be a finite group that acts on a set } X. \text{ For every } g \in G \text{ let }\] \[X^g = \{x \in X: \quad g*x = x \}\] \[\text{ the set of elements in } X \text{ that are fixed by } g.\] \[\text{Let also } |X/G| \text{ denote the number of (distinct) orbits }\] \[G\cdot x = \{ g*x : \quad g \in G \} \quad \text{ for every } x \in X.\] \[\text{Then: } \quad |X/G| = \frac{1}{|G|} \sum\limits_{g \in G} |X^g|\]A known group theory fact is that the orbits of a group action partition the set \(X\), so the above words “distinct” and “for all \(x \in X\)” are not really necessary.

Let’s review the case of counting where no rotation or reflexion takes place. Our answer as we mentioned is \(n^{25}\). If we suppose the trivial group is acting, the action of the identity element \(e\) gives us \(25\) fixed cells (or points). Another way to name it is that we have \(25\) disjoint cycles of length \(1\). See where we are getting at?

For every induced permutation \(\rho_g\), we will be raising \(n\) to the power that is equal to the number of disjoint cycles \(\rho_g\) consists of, including those cycles of length \(1\).

The numbers in a cycle have to be of the same color, this is why one cycle no matter its length will count as one fixed point! To get the desired result, we will have to divide by the group’s order. This is hidden in the no rotation/reflexion case as the group is trivial.

By relying on the Burnside’s Lemma, our problem is reduced to just counting disjointed cycles.

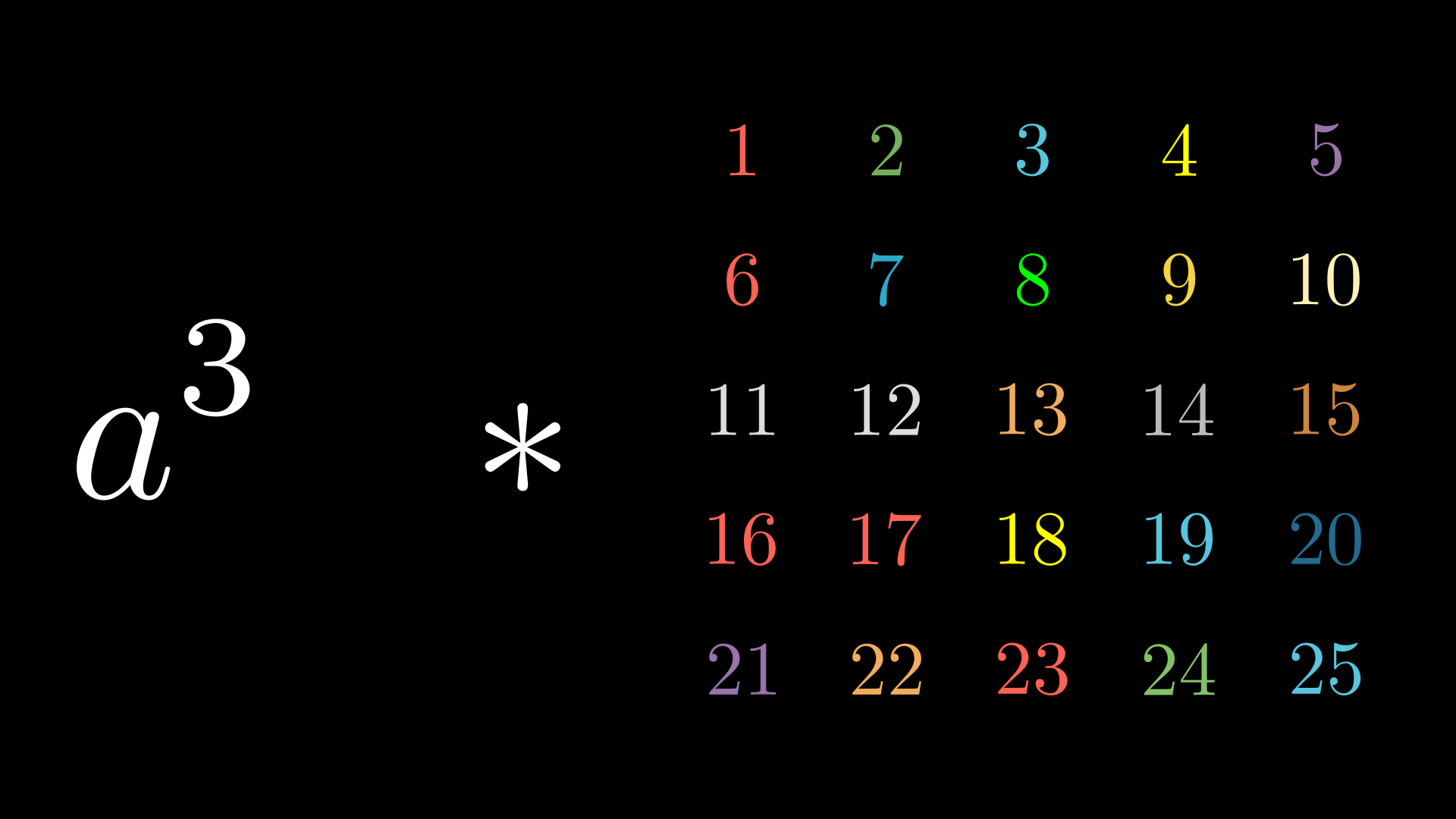

For the sake of the argument, let’s count together the number of cycles after the action of the element \(g = a^3\).

So the induced permutation \(\rho_g\) is equal to

\[\rho_g = (1 \ 5 \ 25 \ 21)(2 \ 10 \ 24 \ 16)(3 \ 15 \ 23 \ 11)(4 \ 20 \ 22 \ 6)(7 \ 9 \ 19 \ 17)\] \[\cdot (8 \ 14 \ 18 \ 12)(13)\]which consists of \(7\) disjoint cycles. Let’s count in a faster way the cycles of the permutation \(\rho_{ba}\).

Since \(b\) is the reflexion on the \(x=0\) axis and \(a\) is the clockwise rotation by \(90^{\circ}\), we are rotating the \(x=0\) axis to the \(y=x\) one and then reflecting. Thus, the cells on the \(y=x\) axis are fixed as we see in the above pictures. Τhe rest of the cells are in cycles of length \(2\). Therefore:

\[\rho_{ba} = (1 \ 25)(2 \ 20)(3 \ 15)(4 \ 10)(6 \ 24)(7 \ 19)(8 \ 14) (11 \ 23)(12 \ 18) (16 \ 22)\] \[\cdot (5)(9)(13)(17)(23)\]which consists of \(15\) disjoint cycles.

So all in all, the induced permutations consist of

\[\rho_e: \quad \text{25 disjoined cycles}\]Those that are purely rotations:

\[\rho_{a}, \rho_{a^2}, \rho_{a^3}: \quad \text{ 7 disjoined cycles }\]Those that contain a reflexion:

\[\rho_{b}, \rho_{ba}, \rho_{ba^2}, \rho_{ba^3}: \quad \text{ 15 disjoined cycles }\]Hence, we are summing up and dividing by \(8\) which is the order of \(D_4\) to get the number of equivalence classes of colorings:

\[|X/G| = \text{number of orbits} =\] \[= \text{ number of equivalence classes of colorings} =\] \[= \frac{1}{8}\left(n^{25} + 4n^{15} + 3n^{7}\right)\]

Thank you for reading! This post was submitted to the SoME1 contest.